For decades, the United States was the undisputed champ of soybean and corn exports. Like Muhammad Ali and Mike Tyson of their eras, U.S. farmers and grain companies dominated the competition.

Now there’s a new king of the ring.

Brazil became the world’s largest soybean exporter in 2013. For the next three years, according to University of Illinois analysis, Brazil and the U.S. traded the title. Brazil emerged as the largest soy supplier in 2017 and hasn’t relinquished it.

U.S. supremacy as the world’s top corn exporter is also in jeopardy. In 2013 and 2019, Brazil nudged out the U.S. as the leading corn supplier due to weather-related production problems in the U.S. and the U.S. trade war with China, respectively. The U.S. fought back for a few years, but Brazil became the corn export champ again in 2023. Increased production, improved grain transportation and better trade relations with major importers were the knockout punches.

“Based on changing dynamics in global agriculture, we need to strengthen our supply chains,” says Chris Pothen, senior vice president, international, with CHS.

Romania, Australia, Argentina, Ukraine and other countries are also growing in importance as grain and oilseed exporters.

Fair fight

The cooperative system is finding ways to stay in the fight.

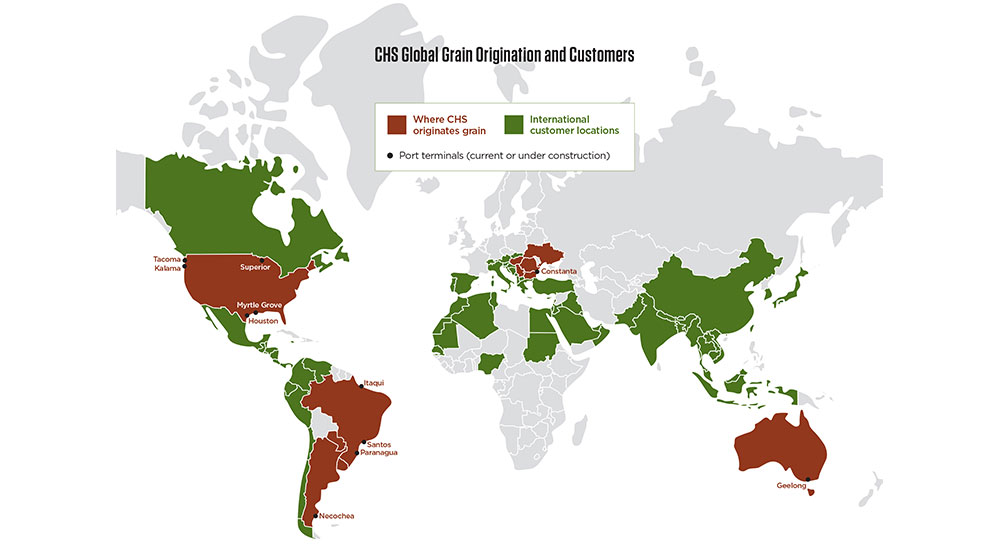

CHS is strategically investing in grain origination and export facilities in the U.S. and in key grain producing regions around the globe to ensure it remains a competitive year-round grain supplier, preserving market access for CHS owners. Expanded capacity in the U.S. and new construction of terminals and other facilities in Brazil, Romania and Australia are key elements in the strategic plan.

“Commodity trade flows are shifting,” says Bryce Banfield, vice president of international sales with CHS. “Many countries around the world are increasing their production, improving logistics and transportation capabilities and providing quality grain to meet market demands. The U.S. has lost export market share of corn and soy, but domestic consumption has increased, primarily for renewable fuels.

“CHS has to change to meet customer demands,” he continues. “If we rely only on the U.S to source and sell grain, we lose relevance.”

CHS is strategically investing in grain origination and export facilities in the U.S. and in key grain-producing regions around the globe to ensure it remains a competitive year-round grain supplier, preserving market access for CHS owners.

Customers first

Jose Barrios, oilseeds processing risk director with Proteinol, a Mexican vegetable oil, sauce and mixed fats producer, says he does business with CHS because of the company’s customer-first approach and the cooperative model. Proteinol buys 600,000 to 800,000 metric tons of oilseeds from CHS annually.

“CHS keeps the human element at the center, looks for fair solutions when challenges arise and adds value to our business to help us achieve mutual goals,” Barrios says.

International grain buyers increasingly want just-in-time shipments to control working capital costs by reducing the need for forward buying and minimizing storage expenses, Banfield says.

U.S. commodities are most competitive on the world market after fall harvest when supplies are high. However, that timeframe has shrunk over the years from six months to as little as three months as other nations increase production and improve logistics, says Brian Schouvieller, senior vice president of ag product lines with CHS.

“Buyers around the world are looking for the best price, logistics and quality. If we are only going to source grain in the U.S. for a few months and the rest of the year the market is South America, the Black Sea or elsewhere, it will be very difficult to be the consumer’s first choice if we aren’t doing business in these regions.

“By providing buyers with quality grain at the right price year-round when they need it, we become a supplier of choice,” he adds. “Our ability to compete globally benefits our owners.”

Grain buyers are requesting multiple offers from different origination areas to lock in the lowest price and shipping cost, says Pothen.

A soybean customer will often ask for offers from the U.S. Gulf, Pacific Northwest (PNW) and South America, he explains. A wheat buyer may seek offers from the U.S. Gulf, PNW, Black Sea region and possibly Australia, depending on the type of wheat desired.

“Having the ability to source grain from different parts of the world is a huge advantage for CHS owners as we serve our customers,” Schouvieller says. “CHS is one of the few multinational companies to source grain from the three major grain-producing regions outside the U.S. [Brazil, the Black Sea and Australia], which sets us apart from the competition. We can pick up incremental margins, which are ultimately returned to owners in patronage.”

That flexibility builds customer loyalty, he adds.

UCG Multiflour, a Panamanian company that procures grain, soybean meal and DDGS (dried distillers grains with solubles) for food and livestock production throughout Latin America, has been a CHS customer for more than 20 years. It buys 500,000 to 700,000 metric tons annually.

“We trust CHS as a supplier to be flexible to meet our needs,” says Juan Antonio Assante, UCG Multiflour procurement manager.

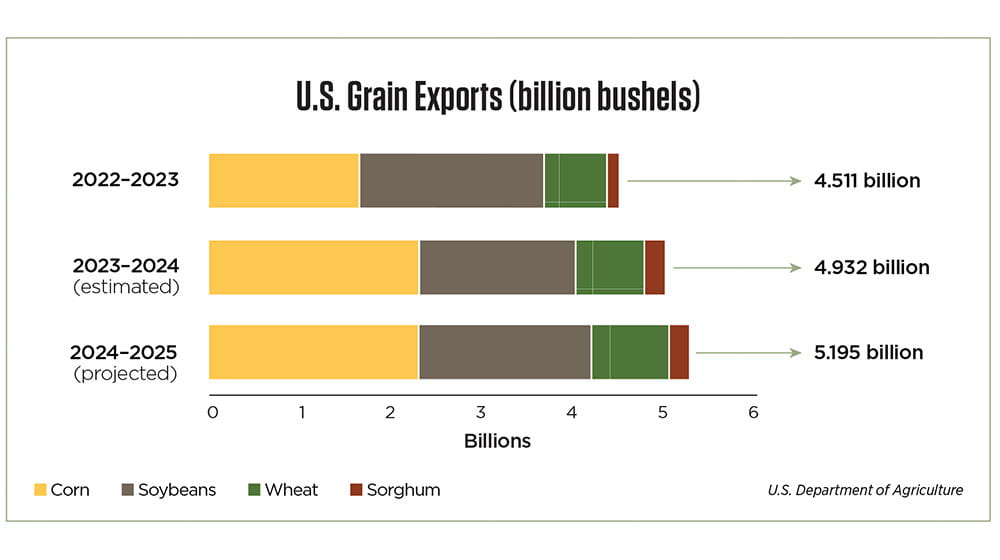

U.S. grain exports have grown steadily since 2022.

Focus on U.S. owners

Anticipating and responding to changing trade flows, CHS has made significant investments in U.S. acquisitions and facility improvements to better serve farmer-owners and customers.

“Our biggest investments and our largest asset profile has been and always will be in the U.S.,” Pothen says. “Marketing U.S. grain and feed products is as important as ever.”

TEMCO, a joint venture between CHS and Cargill, added an export facility at the Port of Houston in 2023 to complement grain terminals in the PNW. Grain produced in the Southern Plains naturally flows to the Texas Gulf for export. The Houston port provides a gateway to the world for those commodities — primarily wheat and sorghum.

In the U.S., CHS purchased several grain assets, three with train shuttle-loading capabilities, from Cargill in 2024 to connect more growers to the global marketplace. And three new train shuttle-loading facilities were built in Minnesota and South Dakota, with a fourth under construction, to ship grain to TEMCO terminals in the PNW.

One of the company’s most significant modernization and expansion projects was finished in October 2024 at Myrtle Grove, La., the southernmost ocean-facing export terminal on the Mississippi River. The $105 million project includes:

- Six shipping bins that improve loading capabilities

- A bulk weighing and grading system

- A dock and barge unloading system

- An independent conveyance system to enhance vessel loading

- An electric-powered crane, or E-Crane

The expansion will increase export capacity through the Myrtle Grove terminal by 30%.

As the U.S. crushes more soybeans to meet soy oil demand, the Myrtle Grove terminal will be able to export more of the resulting increased volume of soybean meal. Chris Ludwig, vice president, feed grains product line with CHS, says the facility is now better equipped to load vessels with more than one commodity.

“Many customers in Latin America don’t need an entire boat of soybeans or corn, but need a ‘grocery boat’ with one cargo hold of corn, another of wheat and another of soybean meal,” Ludwig continues. “The upgrades at Myrtle Grove will allow us to efficiently load multiple commodities and soft products [DDGS and soybean meal] on the same vessel, which will give us a competitive advantage and generate better end-to-end margins in the supply chain.”

With the Myrtle Grove upgrades, CHS is in a better position to serve a shifting customer base, Ludwig adds.

A study by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development indicates China’s role in driving global food and agricultural consumption is waning. Over the next 10 years, the study says China is expected to account for 11% of global consumption growth compared to 31% for India and Southeast Asia.

Soybean meal is loaded into a cargo ship at the CHS export terminal in Myrtle Grove, La.

Brazil emergence

As 2024 began, the world’s population was 8 billion, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. By 2037, the bureau estimates there will be 1 billion more mouths to feed. Demand for animal- and plant-based protein is also increasing as the middle class grows in many countries.

“That incremental growth in demand to feed people and livestock will likely go to Brazil,” Pothen says. “It doesn’t mean the U.S. is any less important, but we need to be there to participate in global grain trade effectively.”

Brazilian soybean exports jumped fourfold from 705 million bushels in 2004 to a record 3.74 billion bushels in 2023, according to University of Illinois economists. U.S. soy exports grew, too, but at a much slower rate, from about 900 million bushels in 2004 to nearly 1.8 billion bushels in 2023.

The Illinois analysis indicates the U.S. accounted for about 60% of global corn exports and Brazil averaged about 6% in the mid-2000s. By 2023, Brazil’s corn export market share had increased to 30%. It was the top international supplier at 2.2 billion bushels compared to nearly 1.8 billion bushels from the U.S.

Corn and soybean acres have been fairly stable in the U.S. for decades, totaling nearly 178 million in 2024, according to the USDA. Brazil’s corn and soybean acreage have rapidly increased the past 10 years from 118 million to 162 million acres, according to the National Supply Company, Brazil’s version of the USDA. The country has the potential to convert another 70 million acres of degraded pastureland to row-crop production, according to the University of Illinois study.

To capitalize on Brazil’s ascension as an ag powerhouse, CHS is ramping up its presence there. CHS has operated in Brazil for 20 years, says Pothen, with offices, grain and fertilizer facilities, and a small ownership stake in a terminal at the Port of Itaqui in São Luis. However, little control over port logistics has often meant longer ship loading and unloading times.

To gain needed control, CHS joined forces with Rumo, Brazil’s largest railroad company, to build a new transshipment terminal at Alvorada in central Brazil. Connected by the expanded Brazilian north-south railway, the just-completed terminal will be a hub for shipping grain to ports.

The Alvorada facility will service CHS and Rumo’s largest joint venture: a new terminal at the Port of Santos in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. The $500 million project is expected to handle 9 million metric tons of grain and 3.5 million metric tons of fertilizer annually. Construction will begin in early 2025 and is expected to take 30 months to complete.

Horacio Ackermann, the South American operations lead for CHS, says the new port and transshipment hub will reduce the time it takes to ship out grain and bring in fertilizer from weeks to days, increasing efficiency and reducing costs.

“There is a lot of value when you control your supply chain,” he says. “We can supply customers with grain and farmers with fertilizer when they need it, strengthening our position as a competitive supplier. We also create structured margins by having the right assets in the right place and not paying for port access.”

Grain volume handled at the CHS transshipment terminal in Marialva in southern Brazil increased 50% in fiscal year 2024 compared to 2023, its first full year of grain origination.

Black Sea boost

Expansion of the CHS Silotrans grain export terminal in Constanta, Romania, is also underway. The facility has been a longtime launching point for grain and oilseeds sold to customers in North Africa, Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

Located on the Black Sea, the terminal primarily handles corn and wheat, plus some canola and barley. It receives grain via rail, barge and truck from Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria and occasionally Ukraine.

“The Black Sea region continues to grow in relevance as a corn and wheat producer,” Pothen says. “Yields have room to grow and there’s not a lot of population growth, so the region is in a good position to increase exports.”

The expansion project will more than double storage capacity to 8.5 million metric tons, improve intake and outtake speed and add technology to simultaneously unload multiple products. Work is expected to be complete by mid-2025.

The goal is to increase CHS export volumes from the Danube River corridor by 30%.

Australia is next

Wheat is the most widely grown crop in Australia, averaging about 25 million metric tons (nearly 920 million bushels) annually, according to the Australian Export Grains Innovation Center. That’s about 3% of global production, but the country accounts for 10% to 15% of global exports, the agency says.

CHS Broadbent, a joint venture with Broadbent Grain, is building a new export terminal at Geelong on the coast of Victoria, Australia, with anticipated completion in 2025. The facility will feature 80,000 metric tons (2.9 million bushels) of storage, fast truck- and rail-unloading capabilities and high-tech ship-loading equipment. It is expected to have annual export capacity of 1.5 million metric tons (55 million bushels).

While CHS Broadbent began as a container-loading business, Schouvieller says the new facility will extend the company’s supply chain in the Asia Pacific.

“We have developed the capacity to export in bulk, but without our own terminal, we weren’t in control of our destiny. This provides that end-to-end capability.”

Electric crane boosts efficiency

A new electric crane or E-Crane at the CHS export terminal in Myrtle Grove, La., unloads soybean meal from a barge. It will also unload barges filled with DDDGS (dried distillers grains with solubles).

The “E” in the trademarked E-Crane is short for “electric” but could stand for “efficient.”

It takes the same amount of energy to power a cell phone charger for one hour as it does to move one ton of ag products with the new E-Crane at the CHS export facility at Myrtle Grove, La. As the first electric crane in the U.S. dedicated exclusively to grain exports, the high-tech machine is expected to reduce operating costs at the port by $200,000 annually.

Since it’s not powered by a combustion engine, the E-Crane will reduce CO2 emissions at the terminal by an estimated 465 metric tons per year. That’s the equivalent of taking more than 100 cars off the road, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

While the environmental and cost-saving benefits of the crane are “amazing,” says Michael Bates, senior director of operations at the Myrtle Grove terminal, he’s more excited about how it will improve terminal efficiency and safety. The crane is dedicated to unload barges filled with soybean meal and DDGS (dried distillers grains with solubles) destined for export. That frees up other equipment to unload grain.

“The E-Crane will cut the time to unload a barge with soybean meal and DDGS and we’ll be able to move more volume through the elevator to load ships,” Bates says. “The crane also has a claw so we can remove and replace barge covers without putting a person on the barge, which eliminates the risk of injury.”

Check out the full fall 2024 C magazine with this article and more.